Around 2012, the use of personality testing was at an all-time high with some experts reporting that up to 70 percent of companies were relying on the tests when making hiring decisions that year. It seemed that personality testing was the latest craze to take over the world of hiring and recruiting, but fast forward four years, and the same report found that the numbers of companies using these tools had dropped significantly.

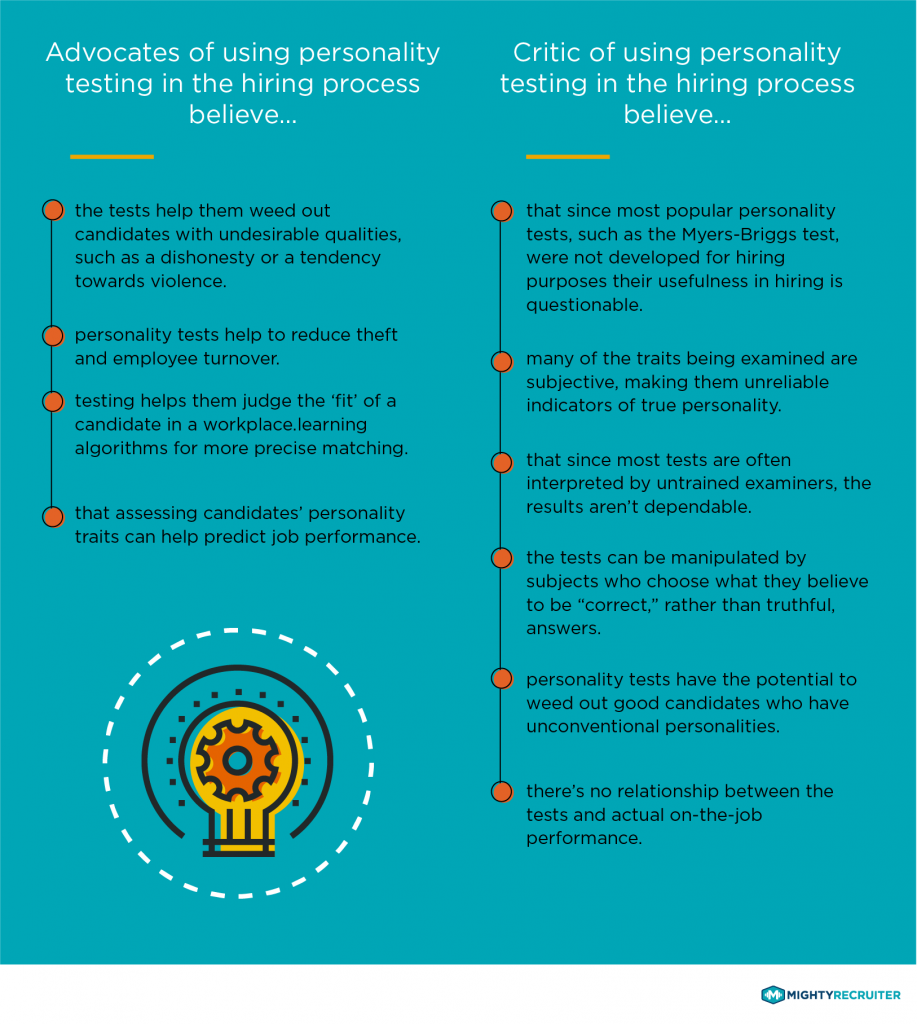

For long-time critics like Annie Murphy Paul, the shift was a long time coming. Way back in 2004 in her book The Cult of Personality Testing, she asserted that personality testing for “captive audiences,” specifically students and jobseekers, was not a valuable tool. She believed back then that the results these tests produced were not true assessments of a person’s personality because the tests themselves were flawed and that they often produced results that were just flat out wrong.

In another criticism of the tests, authors of the paper Using the Myers-Briggs Type lndicator to Study Managers: A Literature Review and Research Agenda concluded that “few consistent relationships between [personality] type and managerial effectiveness have been found.”

Paul revisited the use of personality testing in a 2016 essay. In it, she wrote that “personality testing is an industry the way astrology or dream analysis is an industry: slippery, often underground, hard to monitor or measure.”

Still, she said, the vast number of people she heard from after her book was published were those who wrote her not to agree with her thesis but to defend the usefulness of the personality test. Some, she wrote, even claimed that using these assessments had changed their lives. Those who had joined the cult of personality testing, it seemed, could not be dissuaded.

Still, she said, the vast number of people she heard from after her book was published were those who wrote her not to agree with her thesis but to defend the usefulness of the personality test. Some, she wrote, even claimed that using these assessments had changed their lives. Those who had joined the cult of personality testing, it seemed, could not be dissuaded.

Judy Weiniger, CEO of the Weiniger Group, part of RE/MAX Premier, is one of those employers. Weiniger has been using personality testing for years when hiring employees. Through trial and error, she believes that she’s found a formula that works for her company.

She looks at the results of personality testing as a way of assessing a candidate’s core personality, which helps her decide whether an applicant will perform well in a role.

“I think it would be very difficult to trick these tests and appear to be someone you’re not,” she said. “The questions move very quickly, and they are repetitive, so I trust that the results are accurate.”

Personality testing is not a one-size-fits-all proposition, she said. Weiniger looks for different personality types for different roles. For sales, she said, she looks for people who are highly social and who thrive on human interaction. For an administrative assistant, she would be more apt to choose a candidate who tests as being even-keeled, regimented and detail-oriented. But she doesn’t rely solely on the test results to make her decision. Other criteria – such as references and the opinion of other members of her staff – also hold weight in the decision-making process.

Having personality tests be only part of what decides a person’s suitability for a role is a good thing, at least according to a report published by University of Pennsylvania’s Journal of Labor and Employment Law. That report expressed concern that personality testing could discriminate against particular types of people and that the potential for privacy violations was often built into the tests themselves.

It concluded that “concerns for both job applicants and employees should move us in the direction of attempting to both decrease employers’ reliance on personality tests and improve the tests that are used. Progress along both of those lines will serve the interest of employers by attempting to maximize their chances of making good hiring decisions, as well as the interests of employees in not being unfairly deprived of employment opportunities. It will also help mitigate the potential for other abusive uses of personality tests that might give employers unfair leverage over employees.”

It concluded that “concerns for both job applicants and employees should move us in the direction of attempting to both decrease employers’ reliance on personality tests and improve the tests that are used. Progress along both of those lines will serve the interest of employers by attempting to maximize their chances of making good hiring decisions, as well as the interests of employees in not being unfairly deprived of employment opportunities. It will also help mitigate the potential for other abusive uses of personality tests that might give employers unfair leverage over employees.”

For employers like Weiniger, however, it doesn’t seem that the use of personality testing is going out of fashion any time soon.

“Through trial and error, I’ve taught myself to use these tests pretty well, and I know that they help me find the right people for my business. I’ve even taken the test myself to learn more about how I like to work,” she said. “While, of course, I’ve made some bad hires over the course of my career, each mistake has taught me lessons. And every great hire has given me a model of how to find more talented employees.”

What do you think? Have you found personality testing helpful or harmful in your hiring process? Give us a shout at @MightyRecruiter on Twitter and share your two cents.

MightyRecruiter

MightyRecruiter

Leave a Reply